Digressions on Jazz

Cinema and Sound

Clint Eastwood has done stellar work documenting jazz on film. His biopic Bird, about Charlie Parker, and the documentary Straight No Chaser on Thelonious Monk stand out. Jazz has always had a cinematic quality—Duke Ellington appeared as Pie Eye in the James Stewart classic Anatomy of Murder, for which he also composed the score. Then there was Louis Malle’s 1958 film Ascenseur pour l’échafaud (Elevator to the Gallows), for which Miles Davis improvised the haunting soundtrack in a single session while watching the film’s rushes. The visual and the sonic have always been intertwined in this music.

You can read about my quest as an audiophile here.

Entry Points

For those seeking an introduction to easy listening but real jazz, there’s no better starting point than Bill Evans’s Live at the Village Vanguard with Paul Motian on drums and Scott LaFaro on bass. Evans was almost equally responsible with Miles for the cool sound of Kind of Blue. Another route in: Keith Jarrett’s punchy rendition of “God Bless the Child” with Jack DeJohnette on drums and Gary Peacock on bass, available on YouTube.

Scott LaFaro was another cat who died too young. His work at the Village Vanguard is my go-to album for jazz that is effortlessly listenable and yet such great music. It’s said that Bill Evans was inconsolable when he heard the news of LaFaro’s tragic demise in an accident not long after their date at the Vanguard.

Personal Pantheon

My all-time favorite jazz album would be Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz to Come. Theorizing aside, this is music of great beauty. The standout “Lonely Woman” is sparse and sad like a delicate watercolor.

I love Monk—the staccato and geometric precision of his angular, choppy piano. Coltrane is spiritual and relentless. A Love Supreme rises like a true invocation, rivaled only by Albert Ayler’s Spiritual Unity album. Mingus is large and lumbering, as if his physical size and larger-than-life living had to spill over into the sonic palette of his The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady.

There are so many of them. The best jazz never feels dated. Lennie Tristano was at the Confucius Restaurant what seems like aeons ago, and yet his piano is as fresh, contemporary, and cerebral as they come. Charlie Parker’s Savoy Sessions were done years ago, and yet songs like the playful “Romance Without Finance” remain a joy to listen to.

The Arrival of Modernism

There’s an interesting mention of “A Night in Tunisia” in Whoops by John Lanchester. The book is about the financial crisis, but in his discussion about the apparent incomprehensibility of modern finance, he invokes the tune:

“…like other forms of human behaviour, [finance] underwent a change in the twentieth century, a shift equivalent to the emergence of modernism in the arts—a break with common sense, a turn towards self-referentiality and abstraction and notions that couldn’t be explained in workaday English. In poetry, this moment took place with the publication of The Waste Land. In classical music, it was, perhaps, the premiere of The Rite of Spring. Dance, architecture, painting—all had comparable moments. (One of my favourites is in jazz: the moment in ‘A Night in Tunisia’ where Charlie Parker plays a saxophone break which is like the arrival of modernism, right there, in real time. It’s said that the first time he went off on his solo, the other musicians simply put down their instruments and stared.)”

Understanding the Idiom

Jazz has a taste for dissonance—those crunchy clusters of notes that rub against each other instead of blending. Composers like Wagner or Debussy did the same, but in jazz that rough edge becomes part of the flavor.

Then there’s syncopation, the rhythmic twist that throws the beat off balance. In 4/4 time you expect the first and third beats to be strong, but jazz might stress the “wrong” place, push it ahead, or hold it back. Classical music dabbles in this, but in jazz it’s practically the rule.

Most of all, jazz lives on improvisation. Instead of rehearsing every variation in advance, players know the chords inside out and invent as they go, trusting their ears and instincts. Listeners who know the standards enjoy hearing how a musician bends and reshapes them—sometimes in playful, obvious ways, other times so subtly it barely shows. And sometimes the reinvention can be so far out it grates. I once played someone Kurt Elling’s vocalese version of Coltrane’s Resolution; he thought it was execrable and nearly wanted to punch the artist.

That’s the charm and the challenge. Jazz listeners can also get frozen in time, going back to the music of a certain age again and again, rediscovering new turns in familiar standards. Musicians do the same, circling the old material and reshaping it with fresh ears. The music doesn’t just move forward—it keeps looping back, revealing something new each time you listen.

The Sound of the Bass

Jazz listening audiophiles find something alluring about the sound of the double bass. Nothing competes with the aural pleasures rendered by this refined, mellow, deep, woody, and articulate instrument. I love the compositions by British double bassist Dave Holland. His Conference of the Birds—a title drawn from the celebrated Persian literary masterpiece—features Anthony Braxton and evokes sensations that are delicate, ethereal, and oriental. The more you listen, the more you get drawn into the magic of its mesmerizing music.

Indian Voices

When we speak of Indian or Indian-origin jazz cats, the percussionist Trilok Gurtu, saxophonist Rudresh Mahanthappa, and pianist Vijay Iyer are right on top of the heap, with the latter two often collaborating. The Vijay Iyer trio’s Tiny Desk concert (a wonderful live format from NPR) is something special.

There’s “Calcutta Cutie” in Horace Silver’s Songs for My Father. Although Horace Silver never came to India, he wanted this song to have an oriental sound, and someone wrote that the finger cymbals give the feel of a Bengali religious drum. Not to be outdone, our neighboring country too has inspired “Rawalpindi Blues” in Carla Bley’s Escalator Over the Hill and “Pakistani Pomade” by the Schlippenbach Trio.

There’s an interesting article on the vibrant jazz scene in India of an era bygone at the New York Times India blog. Must have been quite something when stalwarts like Duke Ellington and Dizzy Gillespie played in venues packed to the rafters. Fairlawns, the iconic hotel which seems to have been the venue of many such gigs, has recently been bought by the Oberois of the Elgin group. Jazz must be the last thing on their minds when they begin remodeling it.

Deep Cuts and Discoveries

I’m not a great fan of vocalese, but sometimes when I listen to “Resolution” (in A Love Supreme), my mind seems to get stuck with the lyrics of Kurt Elling. Someone called Jon Hendricks the James Joyce of jazz, and the first occasion I had to listen to him was in a tribute concert to Charlie Parker. He was helped by his family members, and they had put standards like “Billie’s Bounce” to lyrics.

I thought Don Pullen, who played the piano like a percussive instrument (which it is), was quite underrated. I was introduced to him through his works with Charles Mingus (Changes One, Changes Two, Mingus Moves). Later I listened to many of his albums from his prodigious output. Capricorn Rising and Milano Strut are a few I possess.

Speaking of underrated pianists, Mingus himself and the great Nat King Cole come to mind. With some folks, I guess genius comes in spades.

I’ve been listening to Live at Birdland for over a week now. I listen to jazz, repeatedly, till the music becomes familiar, burning a groove in my musical memory. One of the most exciting new albums in jazz is hardly new.It is Coltrane's so called The Lost Album , Both Directions At Once.I rate this very highly in the repertoire of Coltrane albums. There is the sunny “Vilia,” written by a Hungarian composer for an operetta and put there in the manner of “My Favorite Things” but not quite getting there. Various takes of “Impressions,” but the standout song is “Slow Blues,” in whose eleven minutes Coltrane is in his element—sublime and dirty. The support from the cats from his classic jazz phase—Elvin Jones on drums, Jimmy Garrison on bass, and McCoy Tyner on piano—is top-notch. All jazz aficionados should listen to this, if not for the music then for the romance of its discovery.

John Handy was a Mingus alumnus. “A Little Quiet,” from the live album New View, is a beautifully textured, melodically swinging piece. Bobby Hutcherson on the vibes and Pat Martino on the guitar contribute toward creating an incredibly listener-friendly soundscape. This is followed by “Tears of Ole Miss,” a storytelling opus that engages the listener for the entire duration of its thirty-minute-plus playing time.

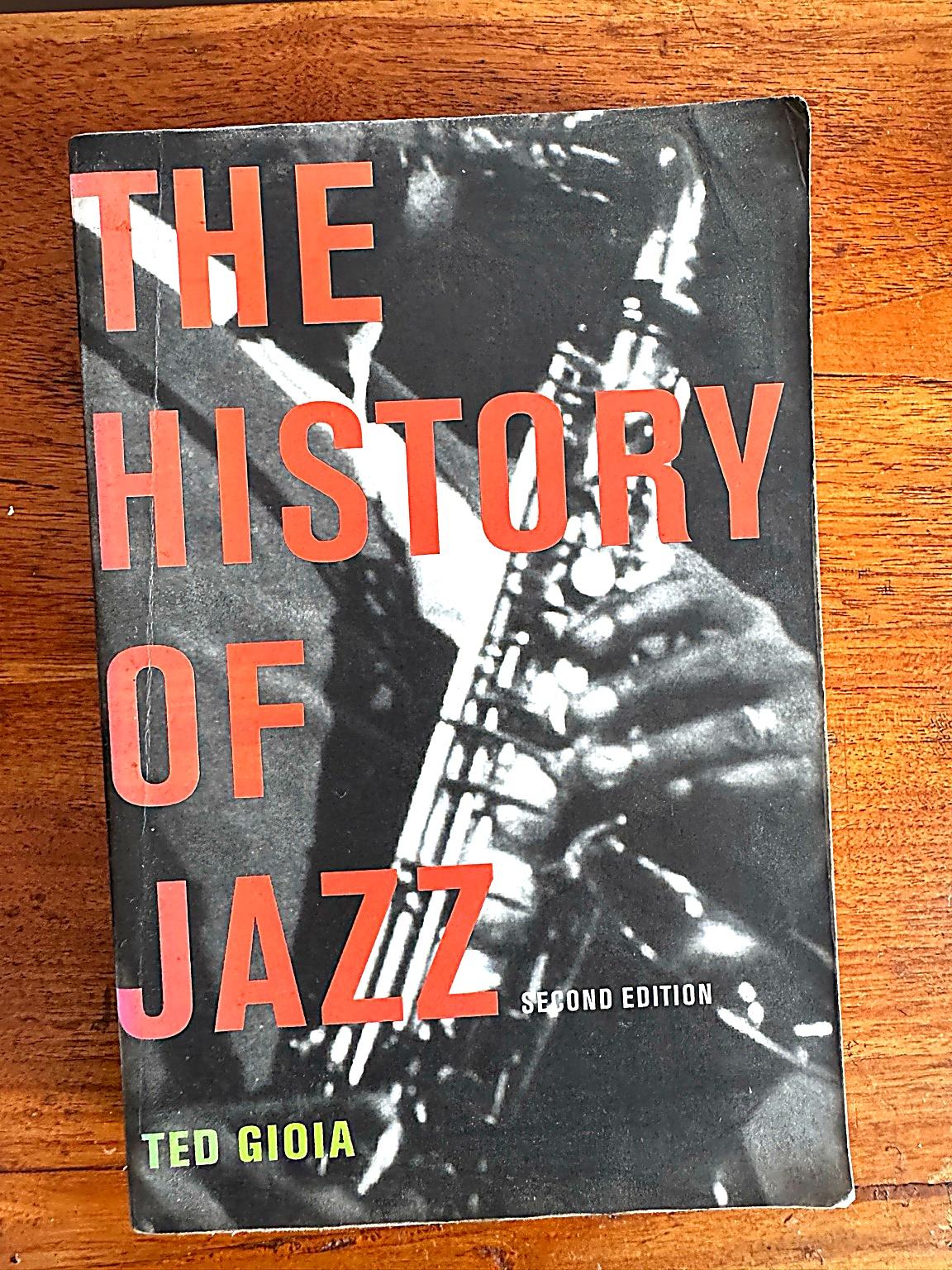

Besides listening to jazz, I have The Penguin Jazz Guide on my Kindle. Recently I read some interesting stuff about The Complete Live at the Plugged Nickel. When someone calls it the Rosetta Stone of modern, post-bop jazz, it makes jazz listening an almost archaeological, investigative affair.

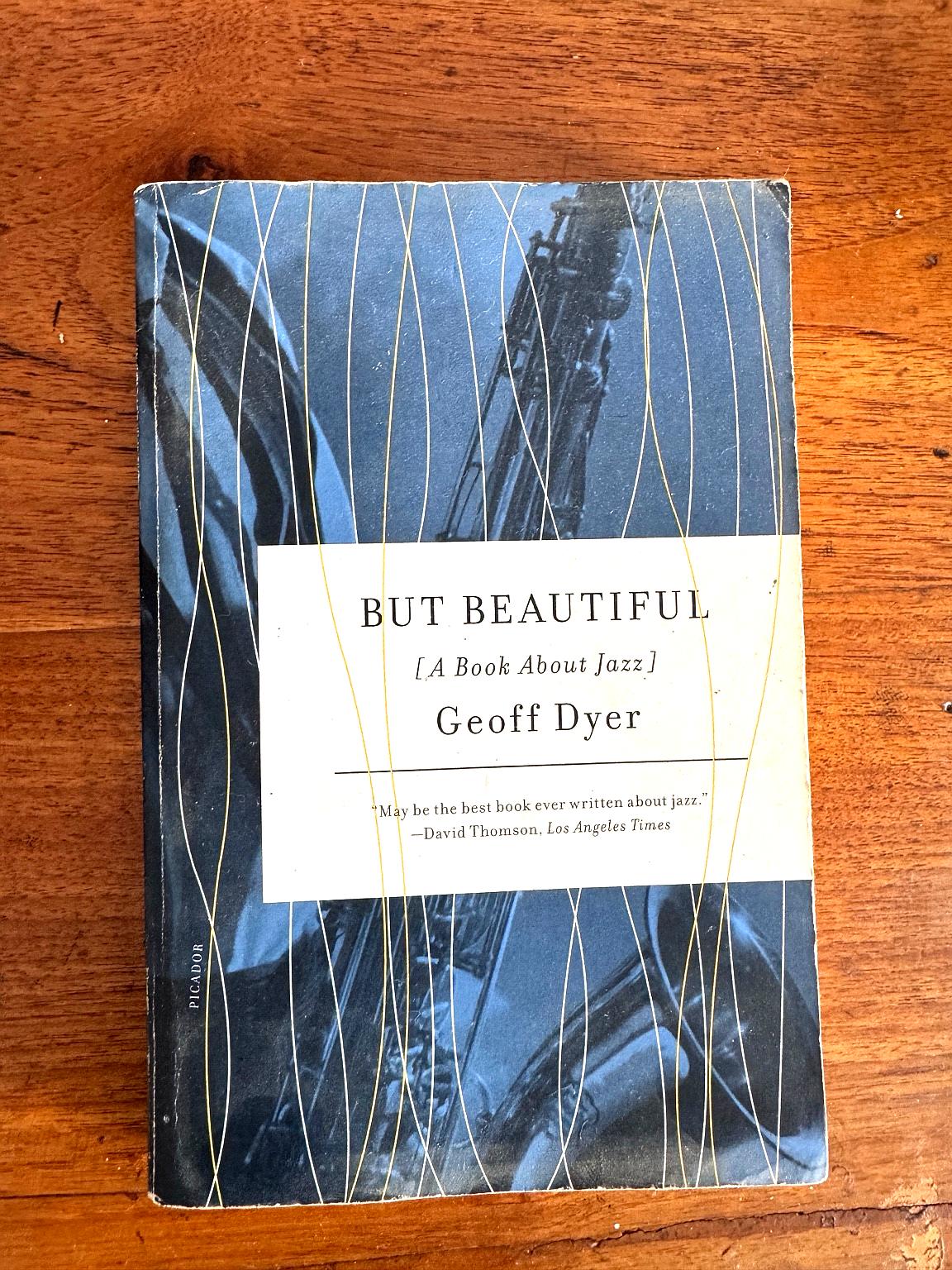

But Beautiful

One of the best books I’ve read on jazz is But Beautiful: A Book About Jazz by Geoff Dyer. It tries to recreate in a rambling, at times stream-of-consciousness kind of narrative the imagined biography of jazz greats like Monk, Mingus, and Ben Webster. For example, everyone knows how Monk took the hit for Bud Powell when cops discovered the latter’s heroin. The story is that Monk was arrested instead of Powell and had his cabaret card confiscated so that he could not perform his jazz publicly. This led to other consequences that Monk fans know about. This episode is reimagined in this fashion.

Note the syncopated prose, the brilliant angularity of the images—almost like chops from Monk’s piano.

“Monk snatched it from him and sent it butterflying out of the window, landing in a puddle and floating there like a little origami yacht.”

“Monk and Bud sat and watched the red and blue lights from the prowl car helicoptering around them, rain sweating down the white glare of the windshield, the metronome flop of the wipers. Bud rigid, holding himself barbed-wire tight.”

“Thelonious Sphere Monk. That you?

—Yeah.”

The word came clear of his mouth like a tooth.

“—Big name.

Rain falling into pools of blood neon.”

“Monk looked down at the rain pattering his photo, a raft in a crimson lake.”

Isn’t that but beautiful?

Coda

William Claxton, the renowned jazz photographer, once said in an interview: “I was up all night developing when the face appeared in the developing tray. A tough demeanor and a good physique but an angelic face with pale white skin and, the craziest thing, one tooth missing—he’d been in a fight. I thought, my God, that’s Chet Baker.”

Such anecdotes abound. Jazz is a music of stories as much as sound, a continuous conversation between the living and the dead, the expected and the surprising. You listen repeatedly, burning grooves in memory, until the music becomes inseparable from your own interior landscape.

Island Discs

On the proverbial island from where presumably there is no escape, one has to take music which one finds fresh, challenging, protean, open to rediscovery every time one listens to them even now. The albums I have chosen have those qualities I believe:

- Ornette Coleman – The Shape of Jazz to Come

- Dave Holland – Conference of the Birds

- Albert Ayler – Spiritual Unity

If I were to take five, I would perhaps add Anthony Braxton’s Saxophone Improvisations (I can imagine myself listening to just its RKRR (Opus 77C) all day long for days), and Coltrane’s A Love Supreme for its spiritual heft, the gratefulness, and the hope it engenders.

Further Viewing